Titanic Shadows in James Joyce's Ulysses, By guest contributor Senan Molony.

James Joyce.

SHIPWRECK is a constant motif in Homer's epic tale of the wanderings of Odysseus. Rather like the tales of Sinbad the Sailor, the perils of the sea are ever-present in the Odyssey.

Small wonder then that James Joyce's landmark novel of the 20th Century, Ulysses - which famously recreates the Odyssey in modern miniature - should contain not only vestiges of shipwreck, but also traces of the Titanic disaster.

Joyce's novel is dazzling and dizzying in its literary and historical allusions, the references ranging across the broad spectrum of the arts and sciences, but also treating all forms of music, modern and ancient languages, and current and historical events as colours for his palette.

Title page of Ulysses. Title page of Ulysses.

He reduced the Odyssey to a single day in Dublin - selecting June 16, 1904 as his canvass. But this date is eight years earlier than the sinking of the Titanic - so how can it can it possible "rearshadow" events which predate the disaster?

The answer is 'easily,' if you happen to be James Joyce. Toning and influencing the book (written from 1914 to 1921) with elements of the Titanic story is as simple as compressing decades of Greek travail into a few trivial hours in Ireland, reducing heroes to quotidian citizens, and transmogrifying the ancient past into the most deceptively ordinary present. Bringing back the future in the same way is a thing most lightly

achieved.

Joyce loved his games, puns and wordplay. His book is an academic and intellectual playground, one which has spouted an endless font of analysis and commentary. Oddly enough, the shipping connections have largely been overlooked.

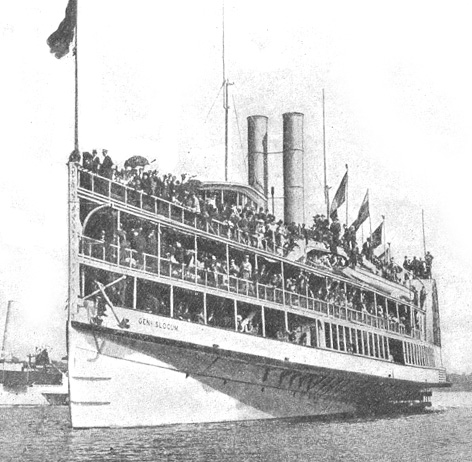

And yet it cannot be accident that the date chosen, June 16, 1904, is the day immediately following the disaster to the General Slocum excursion steamer in New York. The day Joyce selects is the one in which the newspapers contain reports of that floating inferno, which claimed 1,000 lives. Shipwreck is thus, once more, an everyday concern.

The General Slocum. The General Slocum.

The central figure of Ulysses is everyman Leopold Bloom. He buys a newspaper, the Freeman's Journal, containing an account of the Hell's Gate tragedy. Elsewhere in the novel, a priest will walk past a newspaper billboard blaring the news. That night Bloom will read another newspaper, the Evening Telegraph, with a further report of the disaster in New York. The theme is unmistakable.

There are many ornaments of shipwreck in the narrative, from the cameo of a one-legged sailor hobbling the streets on crutches, to the larger idioms of Joyce’s creation of modern allegorical equivalents for the Sirens, Scylla and Charybdis, and so forth.

The author works at all levels in an endless traffic and counterflow of ideas, impressions and emotions, of which shipwreck is just one - the only one considered here.

And he is too fine and disciplined a writer to spoil the subtlety of his craft with a heavy hand. Therefore the Titanic influences are not ill-mannered enough as to be explicit, but are instead part of Joyce's mood-tonality, his artistic pointillism, which builds up the form and shape of the overall from hundreds or even thousands of pieces of mosaic.

Deconstructing the mosaic means paying minute attention to constituent parts, none of which are accidental or of no importance. Thus Joyce's use of the half-phrase that we find half-familiar is used to haunt the text, transferring that which is evoked in the reader to the time and space which the author wishes it to occupy in his work, even for a moment.

The episode of Ulysses that harbours the most seafaring references is the Eumaeus chapter. In the Odyssey this equates to the returning hero describing his adventures to a swineherd of that name once he makes landfall again in Ithaca.

The protagonists of the novel, Bloom and Stephen Dedalus, enter a cabman’s shelter on Dublin’s waterfront after a night on the tiles. It is here that there are repeated references to ships and ice.

The first words uttered are a suggestion for a cup of coffee made to Stephen by Bloom, ‘to break the ice.’ It was ordered “with characteristic sang-froid,” which literally translates as cold blood.

The others in the clientele are “jarvies or stevedores,” with one red bearded bibulous individual staring at them for some appreciable time before “transferring his rapt attention to the floor.”

This man will become a significant narrator in the chapter. He is a sailor named W. B. Murphy (elsewhere ‘Skipper Murphy,’ and D. B. Murphy in an earlier draft.) He could be viewed as an Irish-translated version of Captain E. J. Smith, since Murphy is the most common surname in Ireland, as Smith is in Britain. Murphy also has a beard.

The coffee comes, a ‘swimming’ cup, together with a ‘rather antediluvian specimen of bun’ [antediluvian meaning before the Great Flood of Noah], and the water-based imagery will continue throughout the chapter.

It is now that Stephen Dedalus remarks that ‘sounds are impostures’ going on to list impressive-sounding names such as Cicero and Napoleon, as well as ordinary appellations, like Mr. Goodbody and Mr. Doyle. “Shakespeares were as common as Murphies. What’s in a name?” he asks.

This mention of ‘Murphies’ comes before the red bearded man’s name is known, and portends that he could be an ‘impostor,’ meaning the author’s transfiguration of someone else.

The red bearded sailor, who had his weather eye on the newcomers, boarded Stephen, whom he had singled out for attention in particular, squarely by asking: And what might your name be?

Later the red-bearded one introduces himself:

- Murphy’s my name, the sailor continued, W. B. Murphy, of Carrigaloe. Know where that is?

Queenstown harbour, Stephen replied.

That’s right, the sailor said. Fort Camden and Fort Carlisle. That’s where I hails from.

Joyce has chosen to link Murphy with the Titanic’s last port of call. The sailor will go on to tell some tall tales (in accordance with his parallel in Homer’s Odyssey) remarking, inter alia, “I seen icebergs plenty, growlers.”

Leopold Bloom now begins musing about seafaring in general, commenting in part: “The eloquent fact remained that the sea was there in all its glory and in the natural course of things somebody or other had to sail on it and fly in the face of providence…”

This latter phrase, of course, has distinct Titanic overtones and was not used in connection with previous shipwrecks. In the same meditation Bloom notes that “lifeboat Sunday was a very laudable institution…”

Bloom doubts some of the sailor’s tall stories, “yet still, though his eyes were thick with sleep and sea air, life was full of a host of things and coincidences of a terrible nature…”

There follow references to other great tales of the sea – the wreck of the Hesperus, the Flying Dutchman – such that we know what is being omitted. A private joke between the author and reader, which is confirmed as the two main characters now notice how “the others got on to talking about accidents at sea, ships lost in a fog, collisions with icebergs, all that sort of thing.”

They drift on to the “wreck of the Daunt’s rock, wreck of that ill fated Norwegian barque – nobody could think of her name for the moment” – another coy reference to the name so obviously left out.

But this name is that of the Norge, like Titanic an ill-fated ship, but a Norwegian vessel that will not sink for another twelve days – going down off Rockall on June 28, 1904.

The barque is eventually recalled in Ulysses as the Palme, actually a Swedish ship, which on Christmas Eve, 1895, was lost off Seapoint, Dublin. Fifteen lifeboat men were lost in a capsize going to the Palme crew’s rescue.

Joyce says it happened “on Booterstown strand” with “breakers running over her and crowds and crowds on the shore in commotion petrified with horror.” Here he appears to be mingling the story with that of the Hampton, driven ashore in such a manner in 1901. The mix-up or garbling may be deliberate, as befits the tall stories told in the respective chapters of the Odyssey and Ulysses.

The Palme and the Hampton.

“Then someone said something about the case of the s.s. Lady Cairns of Swansea, run into by the Mona, and lost with all hands on deck. No aid was given. Her master, the Mona’s, said he was afraid his collision bulkhead would give way. She had no water, it appears in her hold.”

This is the last mention of specific ships in this chapter. This incident occurred in March 1904, some twenty miles NE of the Kish bank on Ireland’s east coast. The Mona, from Germany, was taken in tow by the Slateford following the collision, but the Lady Cairns went down with all aboard.

The Times of London reported that on being berthed, the Mona was found to be “but half full of water.” A Board of Trade Inquiry found that the collision happened “because neither vessel acted with sufficient promptitude when they suddenly sighted each other approaching on opposite tacks in a fog.

“The loss of life was caused by the Lady Cairns sinking before the boats on board her could be got ready for use, and the failure of the Mona to send her any assistance. No effort was made by those on board the Mona to render assistance. The Master of the Mona alleged his reason for not sending a boat to the assistance of those on board the Lady Cairns was because he feared the collision bulkhead might give way and his vessel sink before the starboard lifeboat might be ready for use.

“The Court, however, taking into account that his vessel was light, in ballast, and it had been ascertained by sounding the pump and inspecting the fore-hold that there was no water coming in to the hold, strongly condemns his conduct in withholding succour from those on board the other vessel.”

We can see an overtone here of the Mystery Ship which failed to aid the Titanic, whose name is yet unknown.

But Joyce has a final, and spectacular shot in his locker, with one of the characters declaring:

What he wanted to ascertain was why that ship ran bang against the only rock in Galway Bay when the Galway Harbour scheme was mooted by a Mr. Worthington or some name like that, eh? Ask her captain, he advised them, how much palmoil the British Government gave him for that day’s work.

Such a campaign was only mounted by a man named Worthington in 1911, seven years after the date in which the novel is set. And a year later, at the time of the Titanic, he was making this assertion:

GALWAY AS A TRANSATLANTIC PORT

To the Editor of the Galway Express:

Sir - The narrow escape the Titanic had of a collision when leaving Southampton emphasizes the fact that larger and more commodious harbours than those in existence are necessary for the accommodation of the gigantic Atlantic liners that are now being built. The appalling disaster that has overtaken that vessel in her passage to America emphasizes the further fact of the advantages to be derived from the curtailing of the distance in sea passage between Europe and America.

As the service between Galway and Halifax would shorten the sea journey by over 300 miles, it is self-evident that a large percentage of risk would be avoided by the adoption of these two ports, as well as the risk inseparable from the navigation of the Channel.

Yours &c,

ROBERT WORTHINGTON

Salmon Pool, Dublin.

April 16, 1912.

____________

This, then, is the final giveaway about the vessel so constantly hinted at in this chapter.

But there is a further extended metaphor, as Stephen and Bloom leave both the cabman’s shelter and the “elite society of oilskin and company whom nothing short of an earthquake would move…”

In the dark of the street, amid mention of a “striking coincidence,” they nearly collide with a horse which is sweeping the street – and thereby deliberately trying to intercept, not avoid, objects in its path!

“By the chains, the horse slowly swerved to turn, which perceiving Bloom, who was keeping a sharp lookout as usual plucked the other’s sleeve gently, jocosely remarking: Our lives are in peril tonight. Beware of the steamroller.”

A crow’s nest vignette. The horse stops, and Bloom reinforces the iceberg effect by regretting that “he hadn’t a lump of sugar,” (we can see this image plainly) before continuing: “but, as he wisely reflected, you could scarcely be prepared for every emergency that might crop up.”

The layered Titanic innuendo continues as he reflects that any animal of the same size would be ‘a holy horror to face.’ It was “no animal’s fault in particular if he was built that way like the camel, ship of the desert…”

The two men then watched while the “ship of the street was manoeuvring” anew. The horse halted, and placed “rearing high a proud feathering tail.” It next sent three turds from its body while its driver waited humanely, “patient in his scythed car.”

Joyce, deep below the surface, savagely satirizes the Titanic’s last scenes.

An extraordinary incident in world history is reduced to the banal, indeed the scatological. This is Joyce’s stock-in-trade with the whole of Ulysses and the whole of man’s experience.

As a brief commentator on the great myth of April 1912, and writing but a few years later, he effortlessly surpasses the contentions of Conrad, Conan Doyle and Shaw. All this, says Joyce, will pass – in the horse’s case, literally.

Our final glimpse in this chapter is of the ‘captain’ of the ‘ship,’ the man at the poor brute’s harness, watching as the two protagonists leave the scene, just as Captain Smith watched the mystery ship and his lifeboats depart.

Again the character of the driver (this suddenly significant observer) is unnamed - a shadow merely.

“The driver never said a word, good, bad or indifferent.”

And neither did the author. But we can see some, at least, of what he was driving at.

|