|

|

|

Titanic and the Iceberg

|

|

By Roy Mengot

|

|

-

It's been

popular lore in the Titanic story that the

iceberg was spotted 37 seconds before

impact and the ship was too large and

under ruddered to avoid it. This may not

have been the actual fact on the night of

April 14, 1912. A willingness to believe

Titanic couldn't turn quickly may have

served Harland & Wolff and the White

Star Line to hide the fact that the berg

simply wasn't seen until Titanic was

nearly on top of it.

A key definition in

understanding the testimony is the

nautical term 'point'. To describe where

an object is relative to the ship, 90

degrees is divided into eighths. "4 points

off the port bow" is 45 degrees left of

the direction of travel. Two points is

22.5 degrees but people can picture half

of a 45 degree angle easier than they can

work with compass degrees.

The origin of the 37

second figure came when Edward Wilding of

Harland & Wolff and a designer of the

Olympic class ships testified on day 27

before the British inquiry:

25292. Does that

complete the information? - No, there is

a little more information that I think

the Court wishes to have. Since the

accident, we have tried the "Olympic" to

see how long it took her to turn two

points, which was referred to in some of

the early evidence. She was running at

about 74 revolutions, that corresponds

to about 21 1/2 knots, and from the time

the order was given to put the helm hard

over till the vessel had turned two

points was 37 seconds.

25293. (The

Commissioner.) How far would she travel

in that time? - The distance run by log

was given to me as two-tenths of a knot,

but I think it would be slightly more

than that - about 1,200 or 1,300 feet.

Given the speed,

Wilding's numbers for the distance

covered, with some addition drag caused by

the turn, are correct. However, the 37

second time for Olympic is not consistent

with the numbers for Titanic's trials in

the high speed turn. In fact, 37

seconds for 2 points is almost 50%

greater than what Titanic achieved in

her trials off Belfast Lough. His

calculation of 12-1300 feet has also

reenforced the belief that the berg was

spotted at a distance of a quarter mile

(400 meters).

The 2 points of turn

is significant because it helps to

determine how far away the fatal iceberg

was when it was first sighted.

Quartermaster Hitchens was at the wheel of

Titanic during the collision, and while

there were inconsistencies in his

testimony, he remained consistent on the

ship achieving 2 points of turn before the

collision started. Fred Fleet in the

crow's nest also thought the ship had one

or two points of turn in his testimony. Of

the survivors in a position to observe the

events, these two men are the only ones to

comment on the turn.

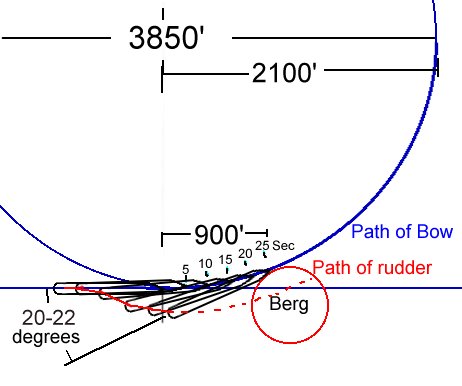

Plotting Titanic's

trials sheds some light on the

maneuverability of the ship. In a standard

maneuver, Titanic was cruising at nearly

full speed, 21.5 knots, and upon passing a

marked point, went into a full hard turn

and the turning radius was measured. The

results showed a 3850' diameter circle

(1174 meters). The forward movement of the

ship was 2100 feet (640 meters) or about

10% more than the radius of the circle.

This was due to the slightly sluggish

start as the rudder was turned and began

to dig in to throw the stern outward as

the ship worked into a full turn.

Figure 1 shows the

turning radius of the circle and includes

the 10% extended curvature on the forward

side of the circle, although it is barely

perceptible. A circle with a diameter of

3850 feet has a circumference of 12,100

feet (3688 meters) and traveling at 21.5

knots or 35.5 feet (10.8 meters) per

second, Titanic traversed the circle in

5.6 minutes (340 seconds). On average, 360

degrees in 340 seconds is just under 1

degree per second.

-

|

|

|

|

Figure 1 - Turning 2 points to the

collision point

|

|

-

|

|

Plotting the tuning

radius out in scale reveals a few

interesting things:

1) The berg as drawn

is roughly 660 feet (200 meters) in

diameter. Since it is not known how large

the berg actually was, it doesn't matter

how large we draw it. For an iceberg

approaching the sizes described in

testimony, Titanic was left of its center,

hence Murdoch ordered a left turn around

it.

2) Getting two points

of turn on the ship can be achieved in

about 25-30 seconds (conservative

estimate) by the data from the trials.

3) It takes 25

seconds to pass the full length of the

ship past a given point at 21.5 knots.

4) At full turn, the

rudder post is about 75 feet (23 meters)

outside the circle made by the tip of the

bow.

Of particular

interest from the testimony was Hitchens'

statement that he turned the ship to port

and scarcely had the helm over when the

collision began. After follow-up

questions, he admitted the helm was full

over when the collision started. He

further stated that he had 'two points' of

turn. Frederick fleet testified the ship

was already turning while he was on the

phone to the bridge, indicating that the

bridge had seen it at about the same time

and was already in action.

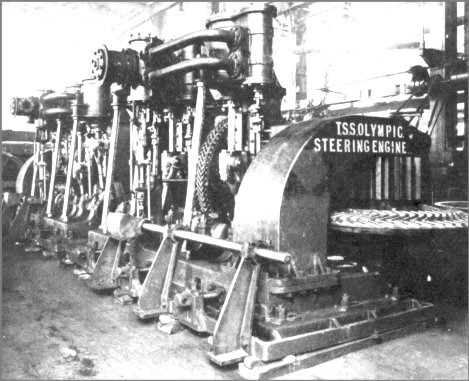

How fast could

Titanic turn its rudder? The steam powered

steering gear atop the rudder under the

poop deck consisted of a primary and

back-up steam engine controlled from the

helm on the bridge or docking bridge. The

steam engine turned gears that could turn

the rudder 60 degrees off center in the

desired direction. From evidence to

follow, Titanic appears to have been able

to get the rudder full over from center in

5-7 seconds.

-

|

|

|

|

Figure

2 - The steam driven steering

gear of the Olympic class ships

|

|

-

|

|

The Porting

maneuver

With the stern

swinging out so wide during a turn on such

a long ship, a maneuver had to be executed

to keep the ship from grinding into the

berg over it's hole length. In the Titanic

scenario this is called 'porting' the ice

berg. To turn left to avoid the berg, 1st

officer Murdoch gave the order 'Hard a

starboard', which meant to starboard the

helm as in an old fashioned tiller, which

was turned opposite the direction you

wanted to go. To swing the stern left and

turn the ship to the right, a 'hard a

port' order would be given. Thus 'porting'

the stern means giving the command to turn

the tiller to port (which turns the ship

right).

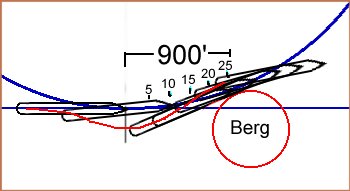

Figure 3 indicates

how this maneuver would appear. The blue

line is the turning radius of the ship and

the red line indicates the path of the

rudder post at the stern if the 'hard a

port' command were given the instant

contact with the berg began. Compare the

path of the rudder to Figure 1 if no

porting maneuver was attempted.

-

|

|

|

|

Figure 3 - 'Porting the

ship' around the iceberg

|

|

-

|

|

When asked at the

British hearings, Quartermaster Hitchens

denied there was a command to turn to

starboard. It's not clear if Hitchens

thought they were asking if the ship

initially turned right or if they asked

about a subsequent porting maneuver. He

volunteered no information and may have

been coached to only answer the question

put to him and say nothing else.

Quartermaster Olliver stated at the US

hearings that the ship was executing a

porting maneuver when he entered the

bridge just after the collision and he

went outside and saw the ship swinging

away from the berg. Seaman Scarrott at the

British hearings also testified he saw the

stern swinging away before the stern had

cleared the iceberg.

What does this say

about the maneuverability of the ship? As

mentioned, it takes 25 seconds for the

ship to pass a given point. If Titanic's

helm was hard over in the turn to port,

then in the next 15 or so seconds after

the start of the collision, the helm was

thrown all the way over in the opposite

direction and the rudder responded. This

indicates that the rudder could be turned

hard over from center in 5-7 seconds.

Bringing the rudder back to center will

stop the turn more quickly as the water

flow aids in straightening the ship.

Getting even part of a turn in the last

7-10 seconds before the berg went astern

of the ship would suffice in clearing the

stern.

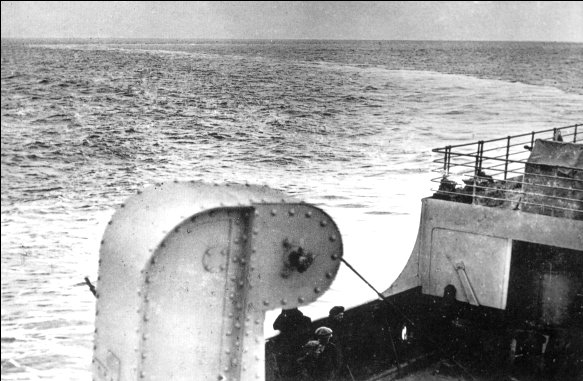

The following photo

was taken by Father Browne during the run

to Queenstown. The ship performed some

lazy-S turns to swing the compasses. As

can be seen by the wake, Titanic appears

to be turning nicely.

-

|

|

|

|

Figure

4 - Titanic performing turns

between Cherbourg and Queenstown

|

| - |

|

The retarded turn to

port upon sighting the ice is not

consistent with the responsiveness of the

ship in the subsequent turn to starboard.

|

| - |

|

Effectiveness

of lookouts

On

a dark moonless night, the main way to

spot an iceberg is by water breaking

around the base. This was not possible for

Titanic due to the extraordinarily calm

weather. While ice bergs generally appear

white, frost diffuses light. If little

light is reaching the berg, then even less

is reflect back to the viewer.

One

of the ways objects are spotted from a

ship is if the form partially blots out

the sky or distorts the horizon. Eye level

from Titanic's crow's nest was about 24

feet (7.3 meters) higher than the bridge.

While this extends the line of sight to

the horizon by a few miles, it had the

side effect that objects on the water will

be below the horizon out to a greater

distance as well. A 70' (21 meter) iceberg

will be below the horizon from the crows

nest for about 3 miles (5 km) from the

ship. From testimony, it appears that

Murdoch on the bridge saw the berg about

the same time the lookouts reported it.

Fred Fleet testified that the ship was

already turning while he was on the phone

to report it.

Captain

Lord on the Californian testified that he

had little experience with ice and all the

reports placed ice along his more

northerly route to Boston. Despite his

admitted ignorance of ice, he placed two

additional lookouts; one on the mast above

the crow's nest and another of the prow of

the ship, lower than the crows nest. As a

testament to the darkness, Californian had

to turn sharply to avoid icebergs, even

though they were going a little more than

half Titanic's speed and had the extra

eyes looking for them. He subsequently

decided to stop for the night.

Engine

effects

4th

officer Boxhall testified that he thought

the engines had been reversed when he

arrived on the bridge moments after the

collision. All of the testimony from

several crewmen down in the engine spaces

indicate a stop order was received, but

the engines were not stopped or reversed

before the collision began. This indicates

that the rudder was receiving the full

benefit of water flowing past from the

ship's speed and the action of the center

propeller.

It

has been discussed that reversing the

engines would have the effect of reducing

rudder effectiveness by interrupting the

flow of water passing the rudder and

removing the force of water coming off the

center prop. While it's not stated as a

condition in Wilding's testimony about the

37 seconds, if the turning exercise

with Olympic also involved reversing the

engines as per Boxhall's scenario, then

the discrepancy between Titanic's

turning performance at the trials and

Olympic's performance can be explained.

The initial loss of speed from reversing

the engines on Olympic would be minimal,

as Titanic's trials also indicated it

would take over three minutes to stop the

ship from full speed.

It

has also been discussed that reversing one

engine would aid in turning the ship.

While this is true, it doesn't become an

issue in the Titanic scenario. Murdoch

knew he needed to turn and then swing back

the opposite way to clear the stern.

Reversing one engine to help the turn to

port would then hamper the swing back to

starboard. Avoiding the obstacle requires

two turns. In any event, time was too

short for a complicated maneuver such as

tampering with the engines. Even the order

to stop could not be carried out in time.

Conclusions

37 seconds does not

fit the profile of Titanic's turning

radius at the trials. A two point turn

could be accomplished in something nearer

25 seconds, assuming the ship achieved a

full two points of turn. This translates

to spotting the ice berg at 900 feet (250

meters) or less rather that 12-1300 feet

(400 meters). Actions on the timeline for

the collision, such as Fleet phoning the

bridge, may have been done in parallel

with turning the ship, shortening the

timeline. Ultimately, this indicates that

the lookouts and Murdoch could not see the

berg until they were almost on top of it.

At the hearings, the White Star Line and

surviving crew were perfectly happy with

all the speculation that the ship was

under ruddered and unmaneuverable. This

speculation, that continues to this day,

just hides the fact that the crew just

flat couldn't see even large objects and

the margin for safety at their speed

wasn't there under the conditions of that

night. Despite the clear conditions, a

reduction in speed was warranted due to

the extraordinary darkness.

|

| - |

|