| Name |

Lifeboat from Titanic |

Lifeboat to Carpathia |

Confidence Level |

|

Newell, Miss Madeleine |

6

(8 votes) 5 (2 votes) |

6

(8 votes) 5 (2 votes) |

4.63 4.00 |

|

Newell, Miss Marjorie Anne |

6

(8 votes) 5 (2 votes) |

6

(8 votes) 5 (2 votes) |

4.63 4.00 |

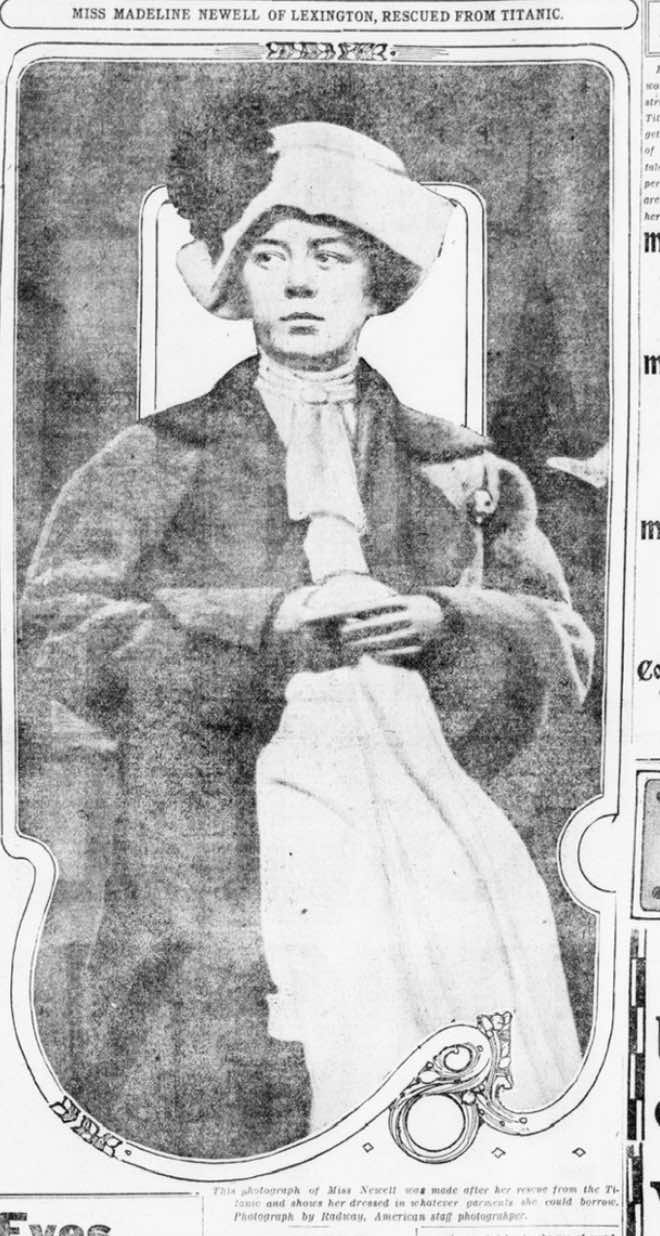

The Newell sisters did not publicly describe their escape for years, and what they stated later in life didn’t always match what was said in 1912. This was compounded by the Boston Globe of April 19, 1912, reporting that the gentleman who accompanied their mother to meet the Carpathia refused to allow the two ladies to be interviewed. The group focused on two lifeboats. The first, number 6, is the one Marjorie claimed to have been in when interviewed in later years. However, several members of the group had been to a talk Marjorie (Newell) Robb had given in the 1980s where she spoke of multiple men in the boat, which doesn’t necessarily match #6. She did say their father saw the first boat away safely before putting them in the next. If Marjorie was on the forward starboard side rather than forward port side, then she may have seen the first boat there, #7, leave, before boarding #5. Therefore, the group concentrated only on boats 6 and 5. The Boston Globe of April 19, 1912, the same paper and date that reported the Newell ladies were being refused to allow interviews, stated, “And in one of the last boats places were made for the Misses Alice (sic) and Madeline Newell of Lexington, but there was no room for their father, A. W. Newell, the president of the Fourth National Bank of Boston. They were among those on the port side, where the rule of ‘Only women and children’ was enforced.” Besides the claim of them being in a later boat, it is noteworthy that the article claims they were in a port boat. However, some details are clearly wrong, such as the reporter misidentifying Marjorie Newell as her sister, who wasn’t even on the Titanic. The New York Evening Post of April 19, 1912, quoted Madeline as saying, “I left the Titanic in a boat at about 2:15 o’clock – that was about a quarter of an hour before the ship sank. We were given four men of the crew for our boat, and after we rowed around in the darkness and among the ice, we moved away from the sinking ship for about a mile in order to avoid the terrible suction… Some of the women had to row until we were picked up by the Carpathia. Two of the sailors went back to look for more bodies after we were safe.” The number of crew more accurately matches #5 than #6. However, two “sailors” going“back for more bodies” more strongly points to one of the port boats that Fifth Officer Lowe brought together, those being #10, #12, #14, #4 and Collapsible D. Boat 5 did transfer at least two men into #7, along with Mrs. Dodge and her son, but they were not crew and they did not return to look for anyone in the water. The Boston Globe of April 22, 1912, described a visit to the Newell sisters by Mayor Charles French of Melrose, Massachusetts. Mr. French later said, “Mr. Newell, according to the statement of his daughters, urged them to get into the boat and positively refused to do so himself, although the boat was far from being full.” With the boat “far from being full” it could have been either #5 or #6, but Mr. Newell would not have had the option of entering #6, making his refusal to get in a moot point. Regardless, the boat being described as not being full suggests an early boat. In an unidentified 1912 newspaper it was stated, “The women in the boat in which the young girls entered owed their escape from death solely to their own efforts, according to the Newell girls. The latter declared they had no remembrance of any men in the lifeboat, and the oars were manned by women, who struggled nobly to move the heavy craft from the danger zone, which they feared when the huge steamer sank beneath the ice-covered water. Madeleine Newell, who is one of the best-known women athletes in this section, was one of the first women in the boat to seize an oar, and throughout the long, dark night, until the rescue ship Carpathia sent its first welcome note from the whistle, she cheered those who were assisting her and kept their courage up. There were nearly thirty women in the boat.” In the Pomona (California) Progress-Bulletin of April 8, 1962, Marjorie Robb told the interviewer that the ship was just starting to list when they got into their boat, and that it was the second to get away. “I helped row. The boat was very badly manned. We were all women and children and there was nobody in command. Finally a crewman who had been hiding in the boat showed himself. He shouldn’t have been there but he was, and finally he took charge.” Mrs. Robb also told the interviewer that the boat leaked and that the crew was inept. The boat being the second to get away could again be #6 or #5, depending upon which side of the ship she left from. A crewman hiding and then emerging to take charge does not apply to either boat. As for the boat leaking, there was water in the bottom of boat 5 and some in boat 6. According to Mrs. Stone, a lady in boat 6, “Our boat did not have very much water, but if there had been we had not so much as a tin cup with which to throw it out.” While Mrs. Robb stated, “We were all women and children,” there were no children in #6, and only one child in #5 until he was moved to #7. Marjorie Robb said in Yankee Magazine, June 1981: “When we arrived on the top, there were really very few passengers about; I believe we were among the first. I believe we were in the second boat to be lowered. The ship was listing rather badly and we were at a great height. The boat we were on had only one boatman. There were no supplies and everything was ill-prepared. My father said, ‘It seems more dangerous for you to get in that boat than to stay here,’ but he hustled us into the boat anyway. We were lowered. Most of the people in the boat were women and they were very frightened; nobody was saying anything. I thought to myself, ‘You have to help where you can,’ so I took hold of an oar and rowed and rowed.” In a 1987 interview while attending the Titanic Historical Society convention Mrs. Robb spoke of a man beside her who had snuck into the boat. He was from New Jersey. This sounds similar to Elmer Taylor of New Jersey who jumped into #5 at the last moment, upsetting some of the people. Madeleine Newell was a graduate of Smith College, and an article in Titanic International Society’s Voyage #47 in 2004 described a letter she had written a friend, Marjorie Gray, which was paraphrased in their alumnae records. “When Madeleine and Marjorie got into the lifeboat they said to their father, ‘Come along too – there’s plenty of room,’ and he said, ‘No, I’ll come later.’ That Titanic lifeboat went down only half-full and Marjorie and a college student (man) helped row it.” The presence of a male who seemed to be a college student seems inconsistent with #6. However, Marjorie rowing does fit a port boat more readily. The problem we faced was the contradictions in the accounts. Both ladies, as well as others, rowed, or only Marjorie rowed. The boat was an early boat, but it left around 2:00 a.m. There were a number of men in the boat or there were no men at all. There were early interviews with Madeleine, yet also a claim that the sisters were prevented at the time from giving interviews. Despite all this, we focused on only boats 5 or 6 for our choices, for the reasons stated above. The Boston American of April 20, 1912 has the following photo of Madeleine Newell. Note her hat. This is only two days after the Carpathia docked in New York.  The following photo is a zoom of the famous photo of lifeboat #6 coming up to the Carpathia the morning of April 15. The circled woman, just forward of Quartermaster Hichens at the tiller, shows a woman with the very same kind of hat.  Another photo of #6 clearly shows that the woman indicated above has the white hat and an oar, and is rowing. In the 1912 New York Evening Post account, Madeleine said she had helped row.  An alternate photo of #6 shows the same woman and hat.  It was brought up that the hat in the later (April 20th) photo may not be the same hat as seen in boat 6, and that Madeleine may have bought it once ashore. After discussion of the photos, we could not prove it was the same hat in the photos, but it raised the confidence level for some of us for her being in #6. After much discussion, seven of the group voted that the Newell girls were in #6 with an average vote of 4.63, while one member split his vote of 3.5 between #6 and #5, and one member voted just 4.5 for #5, giving #5 an average of 4.0. |