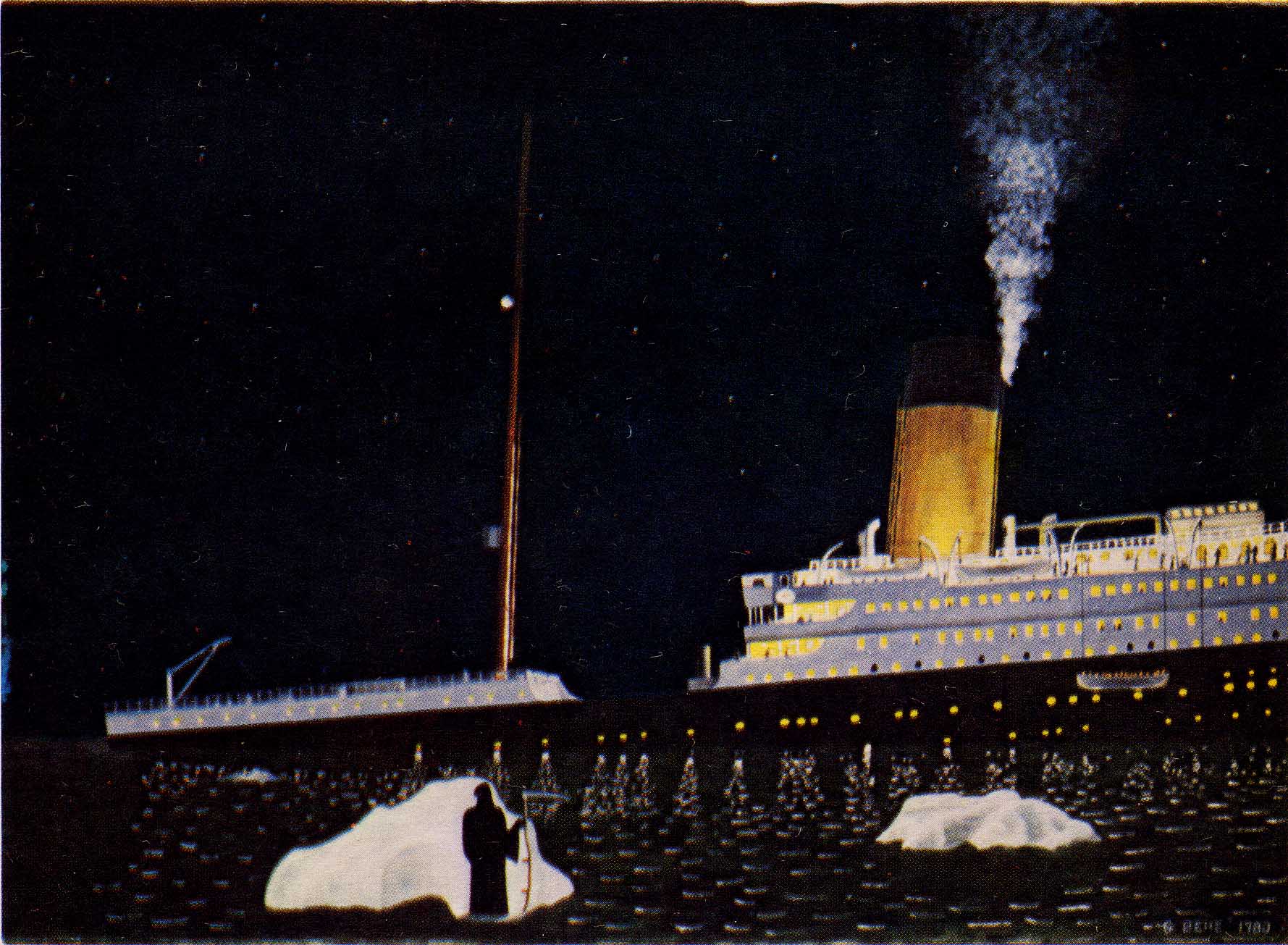

Although it is beyond the scope of this essay to make ironclad assertions about the possible reality of psychic phenomena, two of the author's three books have attempted to shed light on a large number of paranormal-type cases connected with the Titanic disaster. All available historical facts were weighed in order to determine if these cases might have had origins stemming from "beyond" those of normal, everyday occurrences. Although many of the cases ultimately proved to have had prosaic origins, a considerable number of other cases could not be explained away quite so easily. (Readers interested in detailed analyses of the above-mentioned cases are invited to refer to the author's "Titanic: Psychic Forewarnings of a Tragedy" or "Lost At Sea: Ghost Ships and Other Mysteries," which was cowritten with Michael Goss.)

This present essay contains several "unexplained" cases (taken from the above two books) that the author has always found particularly interesting. Whether or not the reader feels inclined to accept these cases as genuine evidence of the paranormal is unimportant; the cases are interesting in their own right and offer fascinating glimpses into the personal lives of several people who - in one way or another - found that their very existence had suddenly become entwined with the sinking of the passenger liner Titanic.

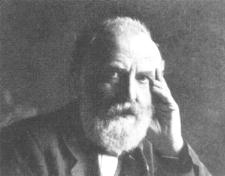

William T. Stead, the well-known crusading editor of the "Review of Reviews," was planning to sail to the United States in April of 1912, having been invited there by President William Howard Taft himself. Mr. Stead was not as excited about his presidential invitation, however, as he was about the huge new passenger liner he would be travelling on.

One day Mr. Stead and an up-and-coming young journalist named Shaw Desmond were walking together along the Strand in the heart of London. Desmond was attempting to discuss an article he was writing for Stead's "Review of Reviews," but the older man kept steering the conversation back to his own upcoming trip. Stead announced that he would soon be sailing on the Titanic, a new ship reputed to be unsinkable, and he waxed eloquent on the vessel's size, speed and other outstanding qualities. Shaw Desmond, on the other hand, had never heard of the Titanic before listening to Stead's monologue on the subject.

The two men continued along the Strand together until, at one point, Desmond drew slightly apart from Stead. It was then that an odd feeling suddenly gripped the young journalist, a feeling that he later described as follows:

"There came to me for the first time in my life, but not the last, the conviction of impending death. In this case, that the man at my side would die within a very short time. It was overpowering and I felt rather helpless, nor did I for a moment associate it with the liner of which he had been speaking."

Shaw Desmond decided not to mention his sudden foreboding of Mr. Stead's fate, and the two men eventually went their separate ways. When Desmond arrived home, however, he was astute enough to jot down a brief notation regarding his premonition about Stead, and he dated it "for future reference."

It was only a few days later that news of the Titanic tragedy reached England. Although there were early rumors that Stead had survived the liner's sinking, Desmond felt certain that the rumors were false and that his own premonition about Stead's fate would prove accurate.

"He is not saved," Desmond told his wife. "He is drowned."

Desmond's foreboding of his friend's approaching death proved to be accurate. William T. Stead met his death on the Titanic.

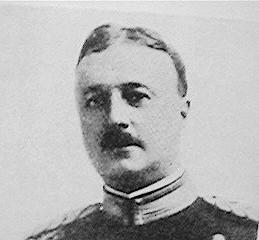

Major Archibald Butt, military aide to President Taft, was also a close friend of Theodore Roosevelt. When the Republican Party could not decide whether Taft or Roosevelt should be its presidential nominee for the 1912 election, Butt was distressed by his divided loyalties; both nominees were his close friends, and he felt enormous pressure at being caught in the middle of their conflict.

Aware that Major Butt needed to get away from these problems for some much-needed rest, his friend Frank Millet, a noted artist, asked Butt to accompany him to Rome in March. Although Butt accepted the invitation, he immediately felt guilty about "deserting" the president during a critical time.

In late February Butt wrote a letter to his sister-in-law in which he informed her of his travel plans.

"Don't forget that all my papers are in the storage warehouse," Butt told her, "and if the old ship goes down you will find my affairs in shipshape condition." Aware that this statement might alarm the woman, he added a good-natured disclaimer: "As I always write you in this way whenever I go anywhere, you will not be bothered by my presentiments now."

Even though Major Butt attempted to make light of the subject to his sister-in-law, it seems clear that he was in fact having very strong forebodings of some approaching personal danger. Even though his friends attributed his uneasiness to the stress he was under, Butt himself told them that he had "never had such a peculiar and constant feeling of impending trouble."

This feeling may have had something to do with what Major Butt did next. In spite of having agreed to accompany Millet to Rome, Butt awoke on February 26th determined to remain in America. He sent wires cancelling all his sailing arrangements, then told President Taft what he had done. The president would not hear of Butt's change of plans, however, and insisted that his aide go abroad as originally planned.

Resigned to making the trip to Rome, Butt drew up his will and asked several of the president's Secret Service people to witness it for him. Butt told these men that he had "an unaccountable feeling that he would encounter some terrible danger before he returned."

A day or two before he left Washington, Butt walked through the White House grounds with a friend, and the two men discussed the major's upcoming trip. Butt told his friend that he "had the strangest feeling he had ever had in his life that he was to be at the center of some awful calamity." Butt said he had had this feeling for several weeks and could not shake it off.

Major Butt sailed for Naples with Frank Millet on March 2, 1912. After delivering messages from President Taft for the pope and the king of Italy, Butt relaxed and tried to build up his strength. Both he and Millet made reservations to return to America when the Titanic sailed in April.

Although Major Butt's presentiments of danger may have continued throughout his vacation, he seems to have felt that, by booking his passage home on the Titanic, he would thereby avoid the last possible source of danger his trip might present. Butt told Baron Carlo Allotti that his vacation had been very pleasant, but that he wanted to get back to America in a hurry.

"I'll get to Washington in time," said the major, "because I am fortunate enough to have a reservation on the new Titanic. When I step aboard the Titanic, I shall feel absolutely safe. You know she is unsinkable."

By the time Butt and Millet arrived in London, however, Butt's presentiments seem to have returned and intensified. A close friend said later that, although usually of a lively and genial temperament, Major Butt was strangely depressed for several days before the Titanic sailed, so much so that his friends were concerned about him.

"I must go along to see Westminster Abbey," Butt told them on April 9th, "because if I miss the abbey now I shall never see it again."

On April 10, 1912 Major Archibald Butt and his friend Frank Millet arrived in Southampton and sailed at noon on the Titanic. Five nights later both men perished when the vessel foundered.

Harry Burrows lived with his mother at 38 Anderson's Road, Southampton, and made his living working on board the great liners which sailed from that port city. Burrows had been anticipating getting a berth on the new Titanic, so much so that he had stayed home for a month so that he would be available when the time came.

On April 10th Burrows bade his mother goodbye and went down to the dock to sign on the great liner. A little while later, however, Mrs. Burrows was surprised to see her son returning to the house. He had not signed on the Titanic after all.

Mrs. Burrows later spoke to the press about this incident concerning her son. Harry Burrows, she said, had "at the last minute changed his mind and come away, for which we are very grateful. I can't explain why he changed his mind; some sort of feeling came over him, he told me."

Isaac Frauenthal was a lawyer living in New York. In March of 1912 he travelled to Europe to attend the wedding of his brother Henry in Nice. The two brothers decided to return to America on the Titanic's maiden voyage and travelled to Southampton to board the great liner on April 10th.

After the Titanic had set sail, Isaac Frauenthal told his brother and new sister-in-law of an occurrence that had made him uneasy. Before boarding the Titanic, he had had a dream. As he described it, "It seemed to me that I was on a big steamship which suddenly crashed into something and began to go down. I saw in the dream as vividly as I could see with open eyes the gradual settling of the ship, and I heard the cries of frightened passengers."

Isaac Frauenthal seems to have regarded this dream as a simple nightmare, but then he had the identical dream a second time.

"I didn't pay much attention to the first dream," he said later, "but when it was repeated I must confess I became a little worried."

When Isaac told Henry and his wife about the two dreams, they laughed and made light of his worries. This may have relieved Isaac's uneasiness a bit, for he later commented on the atmosphere aboard the Titanic:

"I don't suppose any ship that ever took an Atlantic track had a happier, more confident crowd of passengers than the Titanic. The novelty of having a part in the maiden trip of the world's greatest ship appealed to everybody. Then, too, nearly all of us felt that there was no reason to be alarmed or apprehensive about anything."

On the night of April 14th Isaac Frauenthal was lying in bed reading when he heard a long, drawn-out "rubbing noise." He got up to investigate and, hearing that the Titanic had struck something, went to awaken his brother. Henry did not think that the situation was at all serious and returned to bed. Isaac later admitted, "I wasn't sure, having that dream in mind, so made for the deck, looking for Captain Smith or any other officer who could tell me what really happened."

Reaching the deck, Isaac Frauenthal overheard Captain Smith advise John Jacob Astor to awaken his wife, as the passengers might have to take to the lifeboats. Hearing this, Frauenthal returned to his brother's stateroom and again pounded on the door. So great was the general confidence in the Titanic, however, that he had great difficulty in conveying to Henry that there was real danger.

When Henry and his wife finally arrived on deck, Isaac said, "Well, Henry, I wasn't so foolish, was I?"

"Oh," his brother replied, "the boat is too big. It can't sink."

Mrs. Henry Frauenthal was put into a lifeboat, while Henry and Isaac remained on deck. As the lifeboat began to lower, Henry's wife threatened to jump out of the boat if her husband did not join her. On impulse the two brothers jumped down into the lifeboat, and all three Frauenthals were saved.

Eugene Daly, a young Irishman from Athlone, boarded the Titanic at Queenstown along with a group of friends who were also travelling in steerage. It wasn't long before young Mr. Daly told of having had a disturbing dream, and his friend Bertha Mulvihill later recalled the incident:

"It was a funny thing," said Miss Mulvihill. "There was a boy named Eugene Daly from my home town who was with us. When we left Queenstown he told us he had dreamt that the Titanic was going to sink. And every night we were at sea he told us he had dreamt that the Titanic was going down before we reached New York. On Sunday night, just before he went to bed, he told us that the Titanic was going to sink that night. It was uncanny."

Elsewhere, Miss Mulvihill related how Eugene Daly knew the ship would sink because, in his dream, "he had plainly seen the collision with the iceberg."

After Titanic's collision with the iceberg, Miss Mulvihill stood on the slanting deck as the last lifeboat began to be lowered away. A sailor in the boat looked at the young woman and cried, "Jump!" She did, and landed safely in the lifeboat.

Eugene Daly was one of the few male steerage passengers who was fortunate enough to survive the sinking of the Titanic.

[Note: A newspaper reporter quoted Miss Mulvilhill as saying that Eugene "Ryan" was the person who had experienced the premonitory dreams about the Titanic disaster, but Miss Mulvihill's grandson has assured me that she was actually talking about Eugene Daly.]

W. Rex Sowden was a captain in charge of the Salvation Army Corps in the town of Kirkudbright, Scotland. On the evening of April 14, 1912, Sowden had already retired for the night when someone knocked on his door and asked, "Will you please come at once, Captain. Jessie is dying."

Sowden dressed himself immediately and went to the room of the little orphan girl in question. He sat alone with the dying child for a few minutes, but at precisely eleven o'clock Jessie sat upright in her bed. When she noticed Sowden sitting at her bedside, she said, "Hold my hand, Captain. I am so afraid. Can't you see that big ship sinking in the water?"

Thinking that the child's mind was wandering, Captain Sowden sought to comfort her by saying that she had only been having a bad dream. But little Jessie was not to be comforted.

"No," she replied, "the ship is sinking. Look at all those people who are drowning. Someone called Wally is playing a fiddle and coming to you."

Sowden looked around the room but saw nothing unusual. He laid the little girl back into her bed, and she then lapsed into a coma.

Captain Sowden sat with the dying child for several hours and observed no change in her condition, but then, suddenly, he heard the sound of the latch on the bedroom door. Arising, Sowden went to the door and opened it, but saw nobody there. He had the distinct sensation, however, that someone passed by him and entered the bedroom. Sowden rushed back to Jessie's bed and saw that a change had occurred, and that death was only moments away. The little girl suddenly opened her eyes and said that her mother had come "to take me to heaven." Sowden held Jessie's hand for a moment, and the child then died peacefully.

Captain Sowden rose from the bedside and was preparing to go for help when he again heard the lifting of the latch on the bedroom door. Again Sowden opened the door to find no one visible, but he couldn't help coming to the inescapable conclusion that "the mother had departed with her child."

According to Rex Sowden, "Some hours later, the whole world was startled by the tragedy of the Titanic. Among those drowned was Wally Hartley, its bandmaster, whom I knew well as a boy. I had no knowledge of his going to sea or having anything to do with any ship."

In later years, when thinking about the little girl's vision of the sinking ship, Captain Sowden said, "What I thought was hallucination was a vision that stamped itself indelibly on my brain and changed my whole spiritual outlook."

Is it possible that coming events do, sometimes, cast their shadows before them?

Who can tell?