In recent years it has become commonplace for Titanic researchers to express the belief that the Titanic's reputation for unsinkability did not come into existence until *after* the ship went down. They suggest that the Olympic (the Titanic's older sister) was never declared to be unsinkable and that the nearly-identical Titanic was only saddled with this fictional reputation during the frenzied, rumor-filled days that immediately followed the disaster. It is claimed that this 'after-the-fact' reputation for unsinkability was merely part of the myth-building process that has made the Titanic a household name even though nearly a century has passed since her loss.

But is this claim true?

Contrary to popular opinion, there is a considerable body of evidence which proves pretty conclusively that the Titanic (as well as the Olympic) was called unsinkable not only in pre-disaster publicity brochures and newspaper articles but that there was a widespread oral tradition to that same effect -- a tradition that seems to have been promoted by top individuals at both Harland and Wolff and the White Star Line.

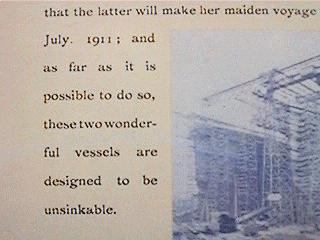

We will begin our discussion by laying to rest the mistaken belief that the White Star Line never commissioned any pre-April 1912 publicity material that described the Olympic and Titanic as being unsinkable. The simplest way to lay this myth to rest once and for all is to illustrate a September 1910 White Star publicity brochure that describes the ongoing construction and future amenities of both the Olympic and Titanic.

Although it is true that the above publicity blurb uses the qualifier "designed to be" when referring to the vessel's supposed unsinkability, the intent of the brochure's claim is unmistakable and must have gone a long way toward impressing seagoing travellers with the absolute safety of these two new additions to White Star's stable of thoroughbreds.

In 1911 a merchant shipping journal called 'The Shipbuilder' described the ongoing construction of the Olympic and Titanic and, at one point, described the watertight doors that were being installed on both ships. The journal said:

"Each door is held in the open position by a suitable friction clutch, which can be instantly released by means of a powerful electro-magnet controlled from the captain's bridge, so that in the event of accident, or at any time when it may be considered advisable, the captain can, by simply moving an electric switch, instantly close the doors throughout and make the vessel practically unsinkable."

Despite the Shipbuilder's introduction of another qualifier ("practically"), the periodical's use of the word "unsinkable" was deliberate and was undoubtedly designed to keep that word in the seagoing public's mind long after the word "practically" had been forgotten.

Interestingly, it is quite likely that the Shipbuilder obtained its information about Olympic/Titanic unsinkability from the White Star Line itself. The present author has discussed this very subject with Bill Sauder, a well-known expert on the construction of the Olympic and Titanic, and Bill states that the Shipbuilder's Olympic/Titanic issue "stands as its weakest effort for a major British passenger ship. Most of the Shipbuilder text has not been written fresh by staff reporters. If you open up White Star publicity brochures of the period, you find that Shipbuilder has simply copied (often verbatim) from the White Star sales sheet. You can find sections that run 50 words before you come across a single difference between the two."

Bill Sauder's discovery that the Shipbuilder relied heavily on White Star publicity material strengthens the likelihood that the periodical's claim that Olympic and Titanic were "practically unsinkable" was merely a paraphrased version of White Star's own claim that the Olympic and Titanic were "designed to be unsinkable."

Although it is true that The Shipbuilder was a specialized nautical publication with a fairly narrow target audience, the reader may be surprised to learn that similar claims of Olympic/Titanic unsinkability (claims that were unquestionably based on White Star publicity material) were published in at least one periodical which boasted an audience that was truly international in scope.

In October of 1910 -- more than seven months before the Olympic commenced her maiden voyage -- the New York Times published a long illustrated article detailing the interior and exterior features of the brand new liner and extolling her sterling qualities to an interested readership. After describing the ship's watertight doors and bulkheads and outlining the measures taken to prevent shipboard fires, the Times concluded its description of the Olympic with the following paragraph:

"In short, so complete will be the system of safeguarding devices on board this latest of ocean giants that, when she is finally ready for service, it is claimed that she will be practically unsinkable and absolutely unburnable."

Since the Olympic's younger sister was briefly mentioned in the New York Times' paean to the Olympic, we may safely assume that the reputation for being "practically unsinkable" was intended to apply to the Titanic as well as the Olympic. Indeed, as we have just seen, there is absolutely no doubt that the seagoing public was first exposed to the Olympic/Titanic 'unsinkability myth' long before either vessel entered the passenger service of the White Star Line.

Before we shift our attention from the Olympic's reputation for unsinkability, it will be instructive for us to review a couple of conversations on that very topic that took place in late 1911 and early 1912. One of these conversations involved the Carpathia's Second Officer James Bisset and a young White Star officer and took place in New York City in early April of 1912. The circumstances surrounding this conversation were described by Bisset as follows:

"Early in April, we docked in New York, and lay ten days at Pier 54 discharging and loading cargo. While we were there, the gigantic liner Olympic arrived. It was the first time that I had seen her. She was berthed at the White Star Pier. I went on board her for a short visit of curiosity, and that was the first time that I ever trod the deck and bridge of a superliner of over 40,000 tons -- a 'leviathan liner,' the first of her kind, in the long-ago of the spring of the year 1912, at the beginning of the Modern Age, with all its marvels and confusion.

"Her promenade deck was a quarter-of-a-mile around. Her bridge was 100 feet from port wing to starboard wing. Her boatdeck was 75 feet above the waterline. Everything was colossal, awe-inspiring, and, as I thought, unwieldy. I was old-fashioned enough to think that she must be "too big to handle" -- but that was only my innocence and perhaps envy. The young White Star officer who showed me her splendors explained that she was unsinkable. She had fifteen watertight bulkheads, the door of which could be closed electrically by pressing a button on the bridge. She had a double bottom."

The fact that the Olympic 'unsinkable myth' was seriously advocated by one of the Olympic's officers to a brother officer is highly significant and demonstrates that the 'unsinkable myth' was apparently believed -- and definitely promoted -- by people who were closely associated with the brand new White Star liner. This fact becomes very clear when we learn that the above-mentioned White Star officer was not the only high-ranking employee of the Line to publicly claim that a vessel of the Olympic/Titanic class was unsinkable; indeed, a far more important White Star officer once expressed views about the Olympic that were identical to those expressed by his subordinate.

(Erie, PA, April 17, 1912). That Captain Smith believed the Titanic and the Olympic to be absolutely unsinkable is recalled by a man who had a conversation with the veteran commander on a recent voyage of the Olympic.

The talk was concerning the accident in which the British warship Hawke rammed the Olympic.

"The commander of the Hawke was entirely to blame," commented a young officer who was in the group. "He was 'showing off' his war ship before a throng of passengers and made a miscalculation."

Captain Smith smiled enigmatically at the theory advanced by his subordinate, but made no comment as to this view of the mishap.

"Anyhow," declared Captain Smith, "the Olympic is unsinkable, and Titanic will be the same when she is put in commission.

"Why," he continued, "either of these vessels could be cut in halves and each half would remain afloat almost indefinitely. The non-sinkable vessel has been reached in these two wonderful craft.

"I venture to add," concluded Captain Smith, "that even if the engines and boilers of these vessels were to fall through their bottoms, the vessels would remain afloat."

One of the most fascinating entries in the history of the 'Unsinkable Olympic' is one which occurred *after* the sinking of the Titanic in April of 1912. The Olympic had been withdrawn from service after the loss of her younger sister and underwent major interior reconstruction in order to make the vessel safe in the event of a major accident. The New York Times of April 3, 1913 describes the result of this reconstruction:

"The White Star liner Olympic left Southampton to-day on her first trip for New York since she was fitted with the double steel bottom and additional bulkheads that are declared by her owners to make her unsinkable. A Southampton dispatch says that her departure recalled the scenes when her maiden voyage began."

[Note: the reader will notice that the Olympic's owners did not dilute their claim about the Olympic's unsinkability by making use of the qualifier "practically."]

The belief that "no one ever said that the Titanic was unsinkable" is so ingrained in the collective mind of Titanic researchers that this very claim is made on the present-day website of Harland and Wolff -- the firm that built the Titanic. Although we have just demonstrated that the term "unsinkable" was indeed used to describe both the Olympic and Titanic prior to April 15, 1912, a great deal of additional evidence exists which proves that a widespread *oral* tradition re: Olympic/Titanic unsinkability was firmly in place prior to the Titanic disaster; indeed, this oral tradition was promulgated by several prominent employees of the White Star Line as well as by a top official of Harland and Wolff itself.

Let us begin our investigation by examining expressions of belief in the Titanic's invincibility that were expressed by a considerable number of passengers and crewmen in the days and weeks prior to the great vessel's departure from Southampton on her maiden voyage; as will be seen, the passengers and crewmen in question included future survivors -- as well as future victims -- of the Titanic disaster.

(New York, April 18, 1912). The night before Captain Edward J. Smith left New York for Europe to take command of the Titanic, he dined with Mr. and Mrs. W. P. Willie of Flushing, Long Island.

At that dinner Captain Smith, according to Mr. Willie, was enthusiastic over the prospects of his new command. He said he shared with the designers of the vessel the utmost confidence in her seagoing abilities, and told Mr. and Mrs. Willie that it was impossible for her to sink. He looked forward then to the most successful days of his seagoing career, and especially dwelt upon the idea that the Titanic'a appearance on the Atlantic marked a high point of safety and comfort in the evolution of ocean travel. He regarded that vessel as one that would stay above water in the face of the most unexpected trials. Even if a part of the hull should be seriously damaged, he said, there need be no doubt that she would reach port.

"From what I know of Captain Smith," Willie said, "he would be the last man to leave the ship if it was sinking."

Not long before Charles Hays and his family sailed for America, Mr. Hays spoke with an English friend regarding his decision to postpone his original sailing plans in order to be able to travel on board the Titanic. The friend replied:

"Well, at least you are compensated in remaining here another week. It is no small thing to see the latest product of the world's engineering skill, at the first real trial, and know all the time that she might be rammed three times without hurting a hair of your head."

The story of Esther Hart's supposed premonition of disaster regarding her family's upcoming voyage to America is well known; Mrs. Hart was convinced that some tragedy was going to befall her family if her husband Benjamin persisted in his desire to relocate the family to Winnipeg, Manitoba. Even though the Harts were originally scheduled to sail on the steamship Philadelphia, Mrs. Hart felt even worse about the upcoming voyage when the coal strike forced Benjamin to transfer his family's passage to the brand new Titanic.

"The Titanic?" Mrs. Hart asked her husband uncertainly. "Isn't that the ship which they say is unsinkable?"

"No," replied Benjamin Hart. "This ship *is* unsinkable."

Margaret Devaney was a young Irish lass who was emigrating to America on board the Titanic. Miss Devaney later recalled: "When I left my home in County Sligo I had a premonition that something was going to happen. That is the reason I took passage on the Titanic, for I thought it would be a safe steamship, and I had heard it could not sink."

Richard Rouse was an English bricklayer who planned to emigrate to America and establish himself there before sending for his wife Charity and their little daughter. Charity Rouse had a bad feeling about the Titanic, though, and she begged her husband not to travel on that ship.

"Charity, don't worry," replied Richard Rouse in a vain attempt to comfort his wife. "It's a brand new ship, and besides, they say it's unsinkable."

Major Archibald Butt was another traveller who had experienced a sense of unease about his trip to Europe. Shortly before he left Rome to board the Titanic, Major Butt was a dinner guest of the Baron Carlo Allotti, Italian Minister to Mexico. The Baron later recalled their conversation.

"He told me that his vacation had been unusually pleasant, but that he feared he had been away too long and wanted to get back in a hurry. 'I'll get to Washington in time,' he said to me, 'because I am fortunate enough to have reservations on the new Titanic. When I step aboard Titanic, I shall feel absolutely safe. You know she is unsinkable.' "

When Lady Lucille Duff Gordon told the White Star booking agent that she was reluctant to book passage on a brand new ship like the Titanic, the agent replied:

"Of all things, I should imagine you could not possibly feel nervous on the Titanic. Why, the boat is absolutely unsinkable. Her watertight compartments would enable her to weather the fiercest sea ever known, and she is the last word in comfort and luxury. This first voyage is going to make history in ocean travel."

Even though the above 'unsinkable accounts' are post-disaster recollections of survivors and friends of victims, there is no legitimate reason for researchers to doubt their veracity -- especially since similar views about unsinkability were expressed in primary documents that were recorded *prior* to the Titanic disaster. The texts of two such documents appear below.

Thomson Beattie, a Canadian realtor, concluded his travels through Egypt and originally planned to sail home to Canada on the Mauretania. Beattie and his friends changed their plans, however, and booked their passages on the Titanic instead; Beattie informed his mother of his new travel arrangements by sending her a postcard which said:

"We are changing ships and coming home in a new, unsinkable boat."

Albert Ervine was one of the Harland and Wolff 'guarantee group' who sailed on the Titanic in order to monitor her performance and correct any malfunctions that might occur. On April 11, 1912, while the Titanic was headed for Queenstown, Ervine wrote a letter to his mother in which he described the vessel's safety arrangements:

"This morning we had a full dress rehearsal of an emergency. The alarm bells all rang for ten seconds, then about 50 doors, all steel, gradually slid down into their places, so that water could not escape from any one section into the next.

"So you see it would be impossible for the ship to sink in collision with another...."

In addition to the above pre-disaster expressions of belief in the Titanic's unsinkability, a number of post-disaster accounts exist which shed light on similar beliefs that were held by various Titanic passengers right up until the very hour of the Titanic's sinking. These accounts -- some of which were written down by survivors before the Carpathia even reached New York -- are instructive and clearly demonstrate how widespread the faith in Titanic's unsinkability had become.

Alden Caldwell, a missionary who was returning to America from Siam, was rescued by the Carpathia along with his wife and son. On April 17, while the Carpathia was still at sea, Caldwell wrote his parents a letter which included the following paragraph:

"As the people did not realize how quick she would go down, there was no hurry and the lifeboats were not full enough. Some of the boats went down with the ship and there were not enough boats in the first place. The 'Titanic' was considered a 'non-sinkable' boat."

On April 30, 1912 Mr. Caldwell wrote a letter to the editor of his college journal in which he said:

"I attribute the wreck to nothing but carelessness. We all thought the boat non-sinkable and I believe that the poor fellows who were lost had hope to the last that she would not sink for many hours."

Kornelia Andrews, a manager of the Hudson City Hospital in Hudson, New York, was rescued by the Carpathia along with her sisters. On April 18, 1912, while the Carpathia was still at sea, Miss Andrews wrote a letter to her niece in which she said the following:

"Oh, my dear, may you never have to pass through such frightful hours. It was 12 midnight when the crash came and we were all in bed. I rushed to my door and saw the ice crystals all over, they having come in through the porthole next to mine and I knew it was an iceberg, but they told us immediately that there was no danger and of course it never entered our heads for one moment that a magnificent ship like the Titanic could sink...."

Margaretha Frolicher-Stehli, who sailed on the Titanic with her parents, was rescued by the Carpathia and wrote a letter to her brother on April 18th while the Carpathia was still at sea. The letter described the Titanic's collision with the iceberg and then said:

"... I lay down again and just left the cabin door open. I relaxed somewhat thinking back on a conversation that I had had with our steward the day before, when I asked him if the lifevests, lying on top of my closet, were good for anything. He had told me the Titanic could never sink, that even the greatest leak would do no harm because of the watertight walls that would be let down in case of an emergency."

Ernst Persson, a Swedish emigrant, was rescued by the Carpathia and, on April 20th, wrote a letter to his family in Sweden in which he said the following:

"They woke us up at 12 A.M. and told us to enter the afterdeck because we had [struck] an iceberg, nobody believed there was any danger, the boat was unsinkable as they said. At that time nobody was worried until they started to send down the lifeboats."

Sarah Roth , a steerage passenger, wrote a deposition describing the circumstances surrounding her escape from the Titanic. Miss Roth and other Third Class passengers had been directed to go to the Second Class deck, but at that point an 'officer' prevented the passengers from proceeding any further. Miss Roth's deposition quoted the crewman as saying:

"I have had orders not to let anybody come up this ladder or the steps on this deck. It is impossible for this ship to sink."

Lawrence Beesley (a survivor who was definitely not prone to overstatement) made the following observations about why so many of his fellow passengers had declined to get into the Titanic's lifeboats:

"But perhaps what made so many people declare their decision to remain was their strong belief in the theory of the Titanic's unsinkable construction. Again and again was it repeated, 'This ship cannot sink; it is only a question of waiting until another ship comes up and takes us off.' Husbands expected to follow their wives and join them either in New York or by transfer in mid-ocean from steamer to steamer. Many passengers relate that they were told by officers that the ship was a lifeboat and could not go down; one lady affirms that the captain told her the Titanic could not sink for two or three days; no doubt this was immediately after the collision.

"It is not any wonder, then, that many elected to remain, deliberately choosing the deck of the Titanic to a place in a lifeboat."

Archibald Gracie's personal account of the Titanic disaster confirmed Lawrence Beesley's statement that the Titanic's passengers were well aware of the vessel's reputation for unsinkability. Gracie wrote:

"...the men's counsel to preserve calmness prevailed; and to reassure the ladies they repeated the much advertised fiction of 'the unsinkable ship' on the supposed highest qualified authority."

Most of the preceding survivor comments about the Titanic's unsinkability were expressed in private correspondence, while the final two comments (Beesley's and Gracie's) appeared in the authors' sober, level-headed recitations of the experiences they had undergone during the sinking of the Titanic. None of the above chroniclers had the slightest intention of creating and fostering public belief in post-disaster legends about the great ship; indeed, these people were only interested in presenting simple, straightforward descriptions of events and conversations that had taken place on board the Titanic just a short time before. There is no legitimate reason why these accounts should not be regarded as accurate descriptions of actual historical events.

When we take into account the diverse national origins of many of the people who (as we have seen) had spoken about, heard about and given credence to the Titanic's reputation for unsinkability, it becomes clear that this reputation was so widespread that it served to reassure prospective passengers in locations as far-flung as England, Ireland, Egypt, Siam, Sweden and Italy. No matter how one looks at it, we're talking about a *very* effective word of mouth publicity campaign whose sole purpose was to reassure the seagoing public that *nothing* could cause an Olympic class vessel to sink.

The above accounts demonstrate pretty clearly that a widespread oral tradition of Olympic/Titanic unsinkability existed prior to the Titanic disaster and that it wasn't until after the disaster occurred that anecdotal accounts of this oral tradition began to find their way into print. The reader might wonder how an oral tradition like this could gain such widespread acceptance among the seagoing public of 1912, but the answer to this question is actually pretty simple. What better way for an oral tradition of Olympic/Titanic unsinkability to take root than for prominent people like Captain Smith to boast about that unsinkability to White Star's passengers (many of whom regularly patronized the Line and could be counted upon to share such information with their associates) as well as to non-nautical friends on shore. The interviews presented in this monograph show pretty clearly that Captain Smith did indeed make such boasts about Olympic/Titanic unsinkability to both groups of people prior to the commencement of the Titanic's maiden voyage.

Interestingly, two additional accounts exist which document crucial 'unsinkability statements' that were made *during* the Titanic's maiden voyage -- two identical sentiments that were expressed by two key people whose opinions were understandably accorded a great deal of weight by the passengers who listened to them..

Let us examine the first of these two accounts.

In 1944 survivor Elmer Taylor wrote an account of his life that included a re-telling of his own experiences on board the Titanic. Taylor recalled the following circumstances which enabled him and his friend Fletcher Lambert Williams to come into close proximity to Captain Smith on the night of April 14th - the night of the sinking:

"Williams was a democratic sort of chap, did not hesitate to move among the high, the less high or lowly, so he selected a table for coffee in the Reception Room next to a table at which Captain Smith was entertaining a party. We were close enough to hear Captain Smith tell his party the ship could be cut crosswise in three places and each piece would float. That remark confirmed my belief in the safety of the ship."

[Note: By this time the reader might well be wondering where Captain Smith obtained the information which encouraged him to boast repeatedly about the Titanic's unsinkability. Surprisingly, it is very possible that Smith obtained his information from an unimpeachable source -- as the following survivor account will demonstrate.]

(April 29, 1912): Mrs. Eleanor Cassebeer declared this afternoon that Thomas Andrews of the firm of Harlan and Wolf (sic), builders of the ship, sat next to her at the table and frequently told her that the steamer had been started before it was finished, but that even though it should be cut into three pieces it would still float.

The reader may have just experienced a feeling of deja vu, because Thomas Andrews told his table companions the very same thing that Captain Smith related to his own table companions -- i.e. that the Titanic would float even if she were cut into three pieces. Is it possible that Captain Smith obtained his ideas about the Titanic's unsinkability directly from Thomas Andrews himself? For what it's worth, the present author thinks that this is a distinct possibility.

It is time for us to shift our focus slightly and ask whether or not the Olympic/Titanic reputation for unsinkability was taken seriously by any other senior officials connected with these ships (besides Captain Smith and Thomas Andrews, that is.) The answer to this question is a definite and resounding "yes!"

On the morning of April 15, 1912 Alfred Stead, the son of Titanic passenger W.T. Stead, awoke to early newspaper reports that the Titanic had struck an iceberg. Despite reassuring bulletins that the ship was still afloat and that her passengers were safe, Stead was concerned about his father's safety and decided to contact Harland and Wolff (the Titanic's builders) and several other maritime experts in order to ask them about the likely results of the collision. These experts all told Stead the same thing -- that the immediate sinking of the ship was almost impossible.

In spite of these optimistic reports, however, Alfred Stead expressed a different view to the London correspondent of an American newspaper:

"Information given me by the builders of the ship and other experts suggests that the Titanic should remain afloat a long time. I myself greatly doubt whether the Titanic is afloat. I am inclined to believe, the opinion of the experts to the contrary not withstanding, that she sank."

On April 22, 1912 Harold Sanderson, a Director of the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company (the owners of the Titanic), read the following statement into the minutes of an urgent White Star board meeting that took place in Liverpool on that date. In that statement Mr. Sanderson said:

"In the 'Titanic' we produced a ship which we believe had only her sister vessel, the 'Olympic,' for a peer, and even this latter vessel was, in some important respects, surpassed by her newer sister. We knew we had put two ships in the service which surpassed all others in size and magnificence. But more than this, we believed that we had made these ships practically unsinkable and absolutely safe for ocean travel."

In the early hours of April 15, 1912 Phillip A. S. Franklin, vice president of the International Mercantile Marine, was being interviewed by newspaper reporters who were asking him about the incoming reports that the Titanic had struck an iceberg. Franklin (like the rest of the world) did not yet know that the Titanic had foundered, and he gave the following statement to a scribbling reporter from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

"We are absolutely satisfied that even if she was in collision with an iceberg, she is in no danger. With her numerous water-tight compartments she is absolutely unsinkable, and it makes no difference what she hits. The report should not cause any serious anxiety."

Mr. Franklin made another such statement to Mr. Smallwood and Mr. Byrne, two reporters for Dow, Jones and Co.:

"There is no danger that Titanic will sink. The boat is unsinkable, and nothing but inconvenience will be suffered by the passengers."

After saying that any wireless reports claiming that the Titanic had sunk would have reached him long before the present time, Mr. Franklin made the following statement to Mr. Trebell, another reporter for Dow, Jones and Co.:

"In any event, the ship is unsinkable, and there is absolutely no danger to passengers."

Mr. Franklin later made a second statement to the aforementioned Mr. Byrne and Mr. Smallwood of Dow, Jones and Co.:

"We cannot state too strongly our belief that the ship is unsinkable and the passengers perfectly safe. The ship is reported to have gone down several feet by the head. This may be due from water filling forward compartments, and [the] ship may go down many feet and still keep afloat for an indefinite period."

If other White Star officers and crewmen were as enthusiastic about Olympic/Titanic safety as were Thomas Andrews, Captain Smith, Harold Sanderson and Phillip Franklin (and testimony at the two inquiries proves that they were), it is reasonably safe for us to conclude that the Olympic/Titanic reputation for unsinkability was pretty widespread prior to the commencement of the Titanic's maiden voyage. Indeed, we *know* that such a myth was widespread due to the number of passengers who either reassured friends and relatives about the Titanic's unsinkability or who were themselves assured of the very same thing by fellow passengers and crewmen. Indeed, it was this preexisting oral tradition of unsinkability that was largely responsible for the confidence that the Titanic's passengers felt in their ship even while she was in the very process of sinking beneath their feet.

We can never know for certain if Captain Smith and Thomas Andrews truly believed the Olympic/Titanic 'unsinkable myth' themselves, but the fact nevertheless remains that both men actively *promoted* that myth to other people. Since there seems to be little doubt that a director of the Oceanic Steam Navigation Company (Harold Sanderson) and the vice president of the International Mercantile Marine (Philip Franklin) both believed the claim that for all practical purposes the Titanic was unsinkable, can the general public of 1912 really be blamed for sharing that same belief?

Vice president Phillip Franklin made one final statement to the press after he finally received the news that the Titanic had gone down with terrible loss of life:

"I thought her unsinkable, and I based my opinion on the best expert advice. I do not understand it."

Mr. Franklin wept as he spoke.

The above accounts have been presented for the reader's consideration because of their deliberate inclusion of one specific word -- "unsinkable." An interesting interview with White Star chairman J. Bruce Ismay has recently come to light in which Mr. Ismay described how that very word had been responsible for influencing his own views about ship safety:

"Everybody learns by experience. One thing that I learned when the Titanic went down is that the laws relating to the preservation of life are not adequate. They were based, no doubt, on the assumption that the great ocean liners, with their highly developed system of bulkheads, were unsinkable. But experience has taught us that at present there is no such thing as an unsinkable ship. I admit that I was among those who were deluded on this point."

Interestingly, at least one paean to Olympic/Titanic safety exists which -- although it avoided using the word "unsinkable" -- nevertheless did its best to convince potential travellers that they would be safer on board the Olympic and Titanic than they would be if they remained on land. In 1910 -- more than a year before the Olympic's maiden voyage -- the Los Angeles Examiner said:

"Though in reality ships, the Olympic and the Titanic, as the two leviathans will be called, will possess all of the conveniences and represent all of the activities of the most up-to-date city. . . . Every safety device known to science will be used, and the passengers will be at least as secure as if they had taken up their residence at a modern hotel for the period required for the trip. Experience has already shown that a big liner is the place where one is safest."

An interesting description of the Titanic appeared in the Cork Examiner on April 12, 1912 -- three days before the Titanic foundered:

"The new White Star liner Titanic, the largest ship in the world, arrived yesterday in Cork Harbor in the course of her maiden Transatlantic voyage to New York. . . .

"In recent [years] ocean travel by each latest outcome of ship construction has gradually been robbed of its terrors and dangers real and apparent which it held for the many, but now, judging by what Messrs. Harland and Wolff were enabled to present to the view of their visitors yesterday, those are bogeys which are set at rest for ever more, and travelling in the future when undertaken on the latest White Star leviathans will be accomplished under ideal conditions and surroundings. . . .

"Safety is a first consideration with all voyagers, and no excellence in other ways can compensate for lack of it. The Titanic is the last word in this respect, double bottom and water tight compartments, steel decks, massive steel plates all in their way making for security, safety and strength. Nothing is left to chance, every mechanical device that could be conceived has been employed to further secure immunity from risk either by sinking or fire. . . . The dangers of the seas are practically non-existent on these latest magnificent vessels."

One important description of the Titanic appeared in the Hampshire Independent in the days immediately following the sinking; the importance of this account stems from the fact that the newspaper in question served the citizens of Southampton -- the home town of the majority of the Titanic's crew:

"The vessel which had been making a splendid voyage up to the time of the mishap, struck an iceberg about half-past ten on Sunday night, and though her construction in the way of bulkheads and other appliances was supposed to render her unsinkable, the impact, which must have been under water, was so great that the vessel's bottom was probably ripped open, and she sank within four hours. . . ."

[The reader will note that the Hampshire Independent did not water down its use of the term "unsinkable" by tacking on the qualifier "practically."]

A second important description of the Titanic was published in the Belfast Newsletter in the days immediately following the sinking. The importance of this account lies in the fact that it appeared in a newspaper that served a major shipbuilding community that was also the home of Harland and Wolff -- the firm that built the Titanic. The Belfast Newsletter stated:

"So elaborate were precautions which had been adopted to guard against accident that it was thought to be practically impossible for her to sink."

The present author submits that the Hampshire Independent and the Belfast Newsletter would never have dared to mention the Titanic's pre-existing reputation for unsinkability if their readerships -- readerships composed largely of professional seamen and professional shipbuilders -- had not once shared that very same belief.

Shared it, that is, until April 15, 1912. . . .

I would like to extend my sincere thanks to my friend Don Lynch for providing me with a copy of the 1910 article from the Los Angeles Examiner. I would also like to thank Mark Baber for sharing his discovery about the White Star Line's post-1912 claim that they had made the Olympic 'unsinkable.'